- —

- Solo Exhibitions

- Group Exhibitions

- Installations

- Moving Image

- Writing

- Publications

- —

- Timeline

- Search

- —

- Contact

Essay by Tina Kinsella

Photography by Michael McLaughlin

Design by WorkGroup

Cover Image: Still from Cassandra's Necklace (2012), film

144 Pages

22cm × 29cm

Hardcover book

ISBN: 978-1-907020-92-6

Published on the occasion of the exhibition Alice Maher Becoming

Irish Museum of Modern Art

Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2

6 October 2012–3 February 2013

Exhibition curated by Seán Kissane

Editor: Seán Kissane

Assistant Editor: Mary Cremin

Design by Peter Maybury

Printed and bound by MM Artbook printing and repro

Prepared by the Irish Museum of Modern Art

First published in 2012 by Irish Museum of Modern Art

Áras Nua-Ealaíne na hÉireann

Royal Hospital, Military Road

Kilmainham, Dublin 8

Ireland

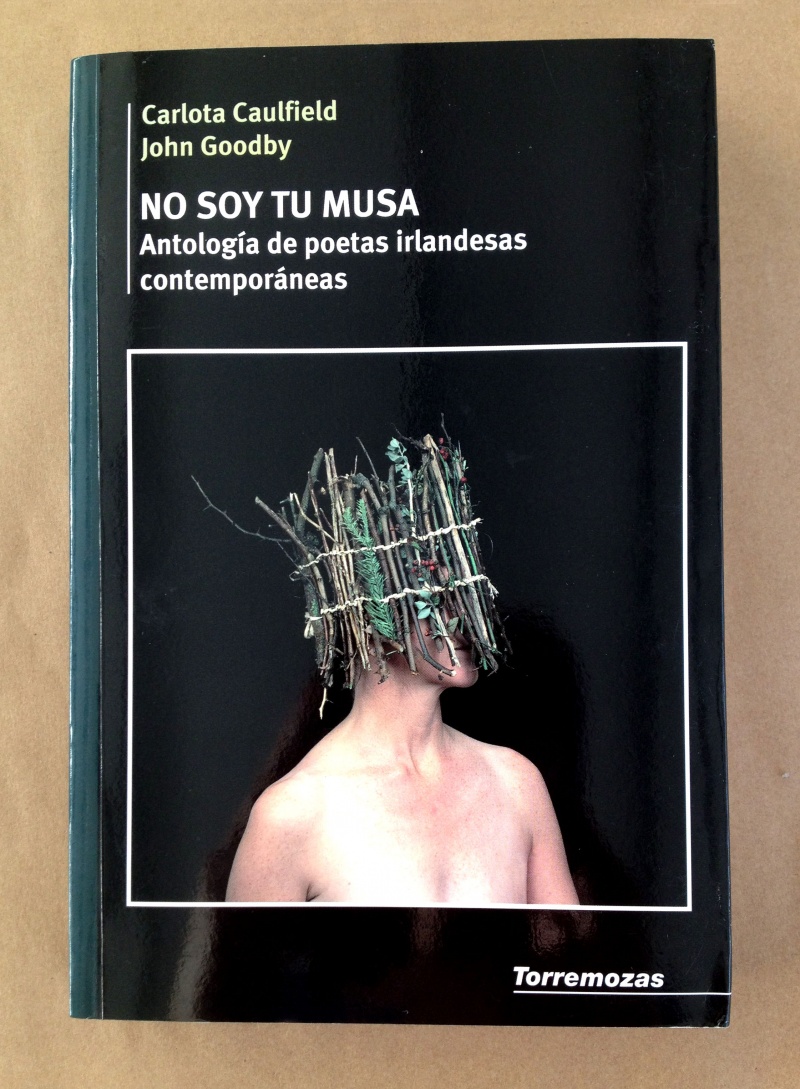

Published in 2007

Drawings by Alice Maher

Poems by Éilís Ní Dhuibhne

Front Cover Image: Mnemosyne (2002)

Back Cover Image: Les Filles d’Ouranos (1997)

Softcover Book

ISBN: 978 0 948723 70 4

Published by the Royal Pavilion, Libraries & Museums, Brighton & Hove on the occasion of the exhibition Alice Maher: Natural Artifice

Organised by Brighton Museum & Art Gallery and shown 27 January–9 April 2007.

Brighton Museum & Art Gallery

Royal Pavilion Gardens

Brighton

Exhibition organised by Nicola Coleby, supported by Jody East

Catalogue designed by Derek Lee

Edited by Nicola Coleby

Design © Royal Pavilion, Libraries & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Essays © The Authors

Printed by Butler and Tanner

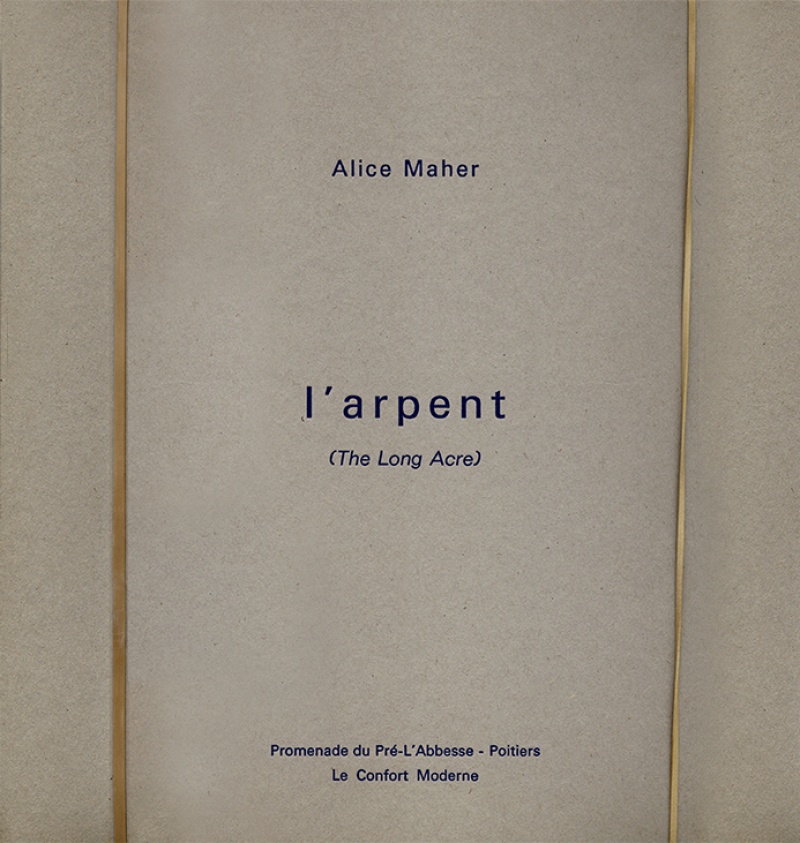

Cover Image: Orsola (2006), installation.

Published 2006

Curator: Vittorio Urbani

Catalogue with texts by Gill Perry and Vittorio Urbani

G. Perry's text Italian translation by Enrico-Paolo Savio

Graphic design by Veronica Marabese, Casali Design Venezia

Photography by Francesco Allegretto

Printed by Grafiche V. Bernardi s.r.l., Pieve di Soligo TV, Italy

Cover Image: Palisade (2003), lambda print.

This publication is associated with Portraits, shown at the Millennium Court Arts Centre in 2003.

Millennium Court Arts Centre

William Street

Portadown,

Northern Ireland

Essay by Carol Mavor

Design by Wendy Williams Design, Dublin

Production by Megan Arney, Belfast

Printed by Nicholson & Bass

Photography by Kate Horgan and John Kellett

© 2003 Alice Maher & Millennium Court Arts Centre

Cover image: Necklaces of Tongues (2000), lamb’s tongues, rope

Published Spring 2001

660 Copies

46 Pages

Hardcover book

ISBN: 0-906630-11-8

Printed offset and letterpress on Cartiera di Cordenons Caneletto paper.

Digital formatting of colour work Joe Kenny, Fethard .

These texts and images are taken from notebooks and sketchbooks 1991–2000 with the exception of Continuous Drawing II, 2000, Mantle, 2000 and Gorget 2000, courtesy Nolan Eckman Gallery, New York, Leaking Head, 2001, together with the title work Necklace of Tongues, 2000.

The endpapers are taken from the name-panels of family tombs m Munster and Leinster written by the artist, with her left hand.

Cover: Detail of Gorget (2000), chrome-plated bronze

46 pages

20cm × 22cm

Softcover book

Published 2000

Exhibition 20 September–28 October 2000

© Copyright 2000 Nolan Gallery

560 Broadway, New York

Design by Jens Jahn, Munich

Photography courtesy of Nolan/Eckman Gallery

Printed and bound in an edition of 600 copies by Passavia Druckservice GbmbH, Passau, Germany

Cover Image: Sir John Everett Millais, Two Figures on the Ground (detail) and Alice Maher, Coma Berenices (detail)

Hardcover Book

ISBN: 1-901702-09-X

Published by the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, 1999

Charlemont House,

Parnell Square North,

Dublin 1,

Ireland

© Alice Maher and the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art Dublin 1999

Photography by John Kellett

Designed and produced by Creative Inputs

Colour reproduction and printing by Nicholson & Bass

Catalogue co-ordination Christina Kennedy and Maime Winters

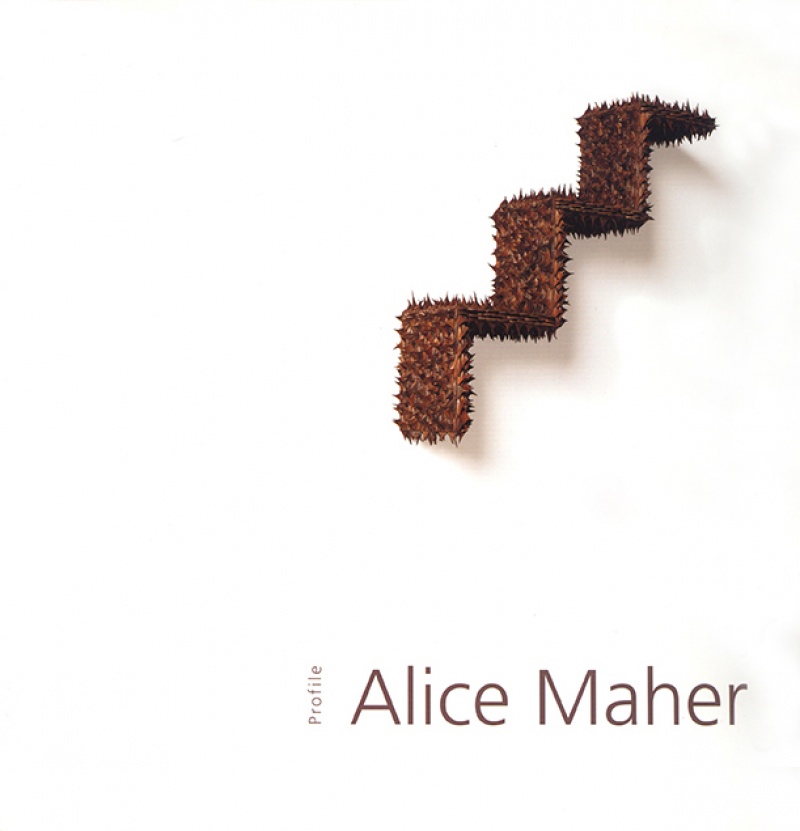

Cover Image: Staircase of Thorns (1997), rose thorns and wood.

Back Cover: Venus (1997)

ISBN: 0946641-935

Published as part of Gandon Editions’ Profiles series on Irish Artists

© Gandon Editions and the artist, 1998

Gandon Editions, Oysterhaven, Kinsale, Cork, Ireland

Essay: Medb Ruane

Editor: John O’Regan

Assistant Editor: Nicola Dearey

Design by John O’Regan (© Gandon, 1997)

Production by Gandon

Printed by Nicholson & Bass, Belfast

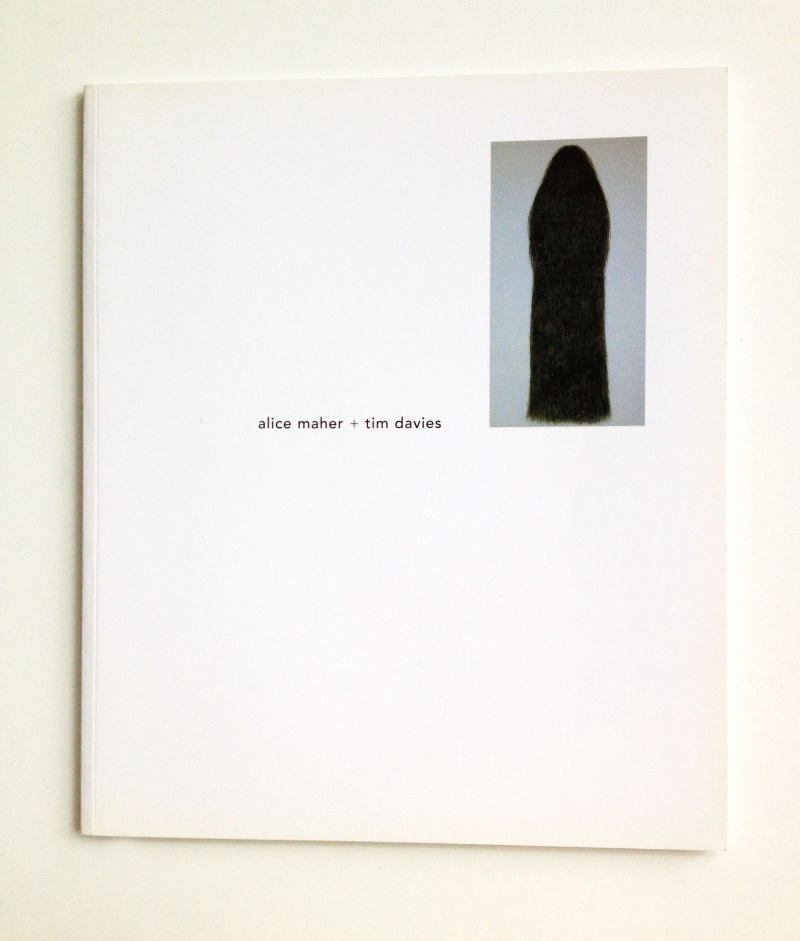

Cover Image: Ombre I (1997), charcoal on paper.

Softcover book

ISBN 0-906860-40-7

Published 1998

First Impression 1998 in an edition of 600

© Oriel Mostyn, Sue Hubbard, the artists, 1998

Translation: David Andrews

Design by View

Essay: Sue Hubbard

Exhibition organised and toured by Oriel Mostyn Art Gallery,

12 Vaughan Street, Llandudno, UK

Softcover Book

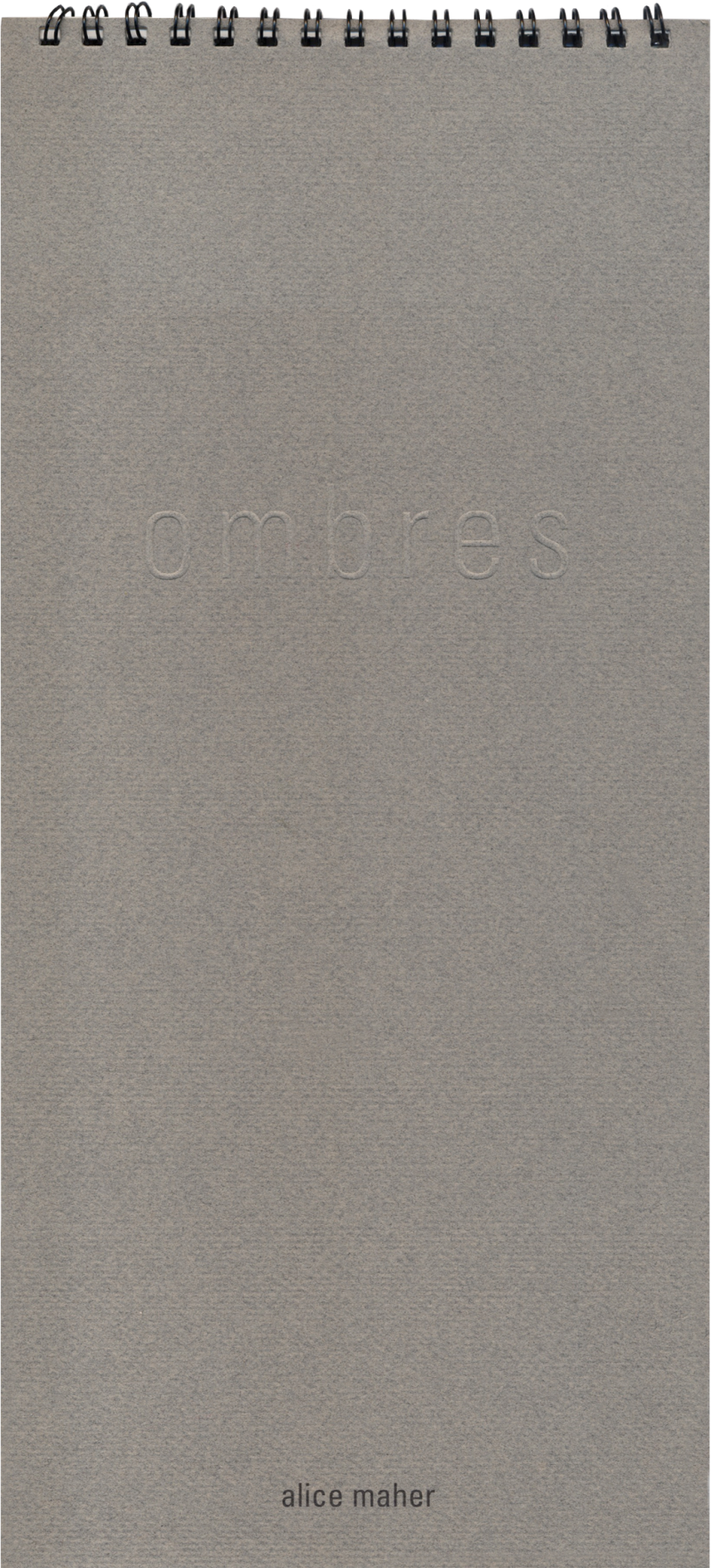

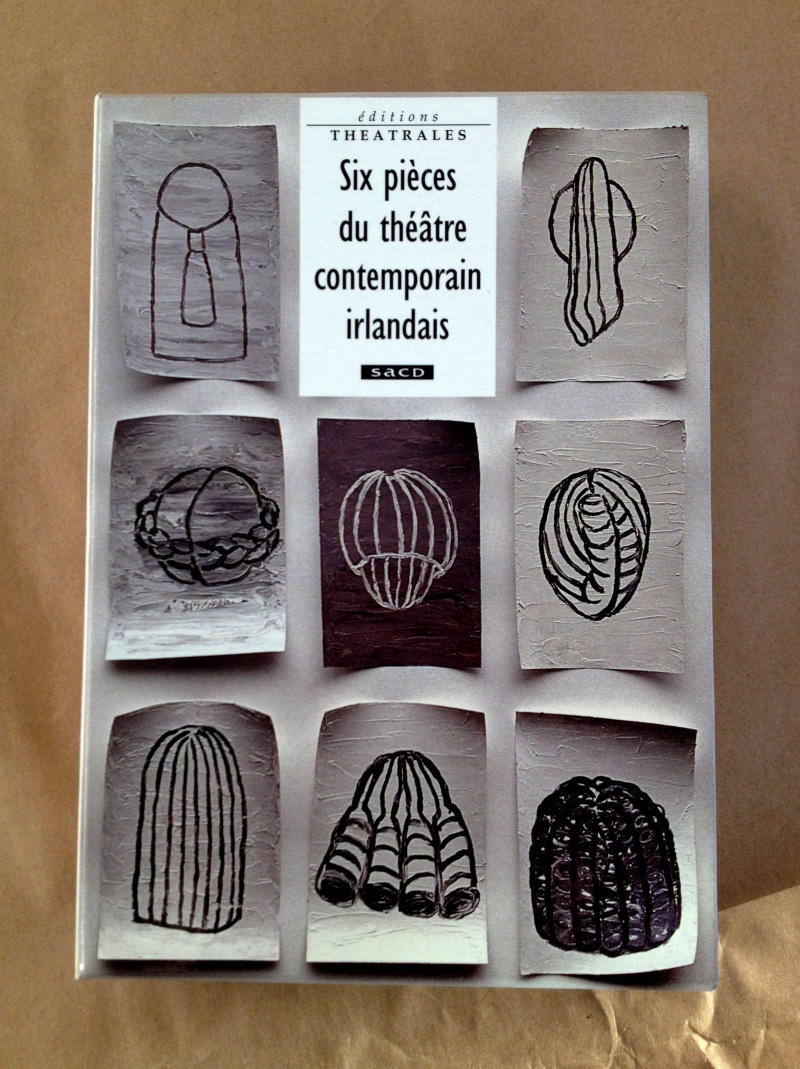

Softcover Book

Published 1996

Designed by Alice Maher

Prepared by Marc Charpin the Cardaillac Stone workshop, Royaumont

This notebook is made in the context of the residence Credac Alice Maher (Imaginaire Irlandais) in June 1996, at the occasion of the exhibition from 28 March to 23 June 1996.

Cover image: Familiar I (1994), acrylic on canvas

Softcover Book

Published by The Orchard Gallery & The Douglas Hyde Gallery, 1995

Orchard Gallery ISBN: 0-907797-81-4

Douglas Hyde ISBN: 0-407660-52-5

© The authors, the artist and the publishers.

Design and Production by Wendy Williams and the Artist

Typesetting by Wendy Williams

Photography by Denis Mortell and Richard Kelly

Reproduction and Printing by Nicholson & Bass

You do not need to know my name but:

I am Mary, Amina, Penelope, Brigid,

Persephone, Frida, Maebh, Makeda,

Sojourner, Granuaile, Cassiopeia, Nan

I am Hecate, Rosa, Lakshmi, Aphra

the X-Case Girl; the women given letters not names,

Sappho, Marsha, Maura, Edna,

Green Tara, Black Madonna

I am the first girl child they put in the septic tank

Come to the loud, feral

Herland, SheLand, Theyland.

A Queenopolis, Cisopolis, Transopolis

A Republic of personhood.

I am the map.

We are the map.

1

At the port of Slag Island

they asked for my papers

and took me to a room

as I did not meet the levels of

submission they required.

Levels they measured with

a taut strip of tape;

whose units were

the width of God’s finger.

After hours of interrogation,

they stamped my passport with a

black benchmark smudge.

So I went to Slag Heap

to seek out my sisters.

A pit, girls.

They offered you a pit instead of a universe,

a colliery of sin.

What do they get?

Wild oat fields.

What do you get?

An empire of dirt.

And you burn red

burn white hot

burn black ash.

Woodcuts of cloud, a sky feathered

like smoke from a fire

no longer tended.

2 Archipelago

The sky shouts in blues and greys,

white-capped waves bellow in teal.

The horizon’s language is

A mother tongue of the

sensible (horizon)

rational (horizon)

celestial (horizon).

The tongues of every bell wagging,

A campanile story.

*

Can you hear Wrens in the hedges

counting coins and pentacles?

Shillings in oiled hands.

Listen hard, across the city.

Hear pillows being plumped

to smother the Syphilis Girls

of the Locke Hospital.

3 Lilith’s Garden

We carve Fallopian furrows,

readying the earth to dig for children.

wearing crowns of Pomegranate twigs.

Infants nestled in velvet peat

not tanks or graves,

Thanks be to god.

Responsorial, hypocritical.

This land of labour,

of women’s fingers,

crooked and worked

to the silken bone

a choreography of wax

on parquet floors,

scrubbing in globes.

Diurnal, Nocturnal

on the moons of their knees.

Arthritic offerings doomed to fossilise.

Waxing, waning,

Did you know gibbous means hump?

You could fuck the moon if you wanted to -

But only when the floor gleams moonbeams.

4

On Ráth na Marbh

they tied women to horses,

then tied them to steering wheels

and forced Sunday drives

to checkpoints.

A Semtex queen.

Bombs go off in women’s

bodies all the time.

An era of walks

by the Metaller,

A dog stranded on the weir.

Maelruan, Glenview,

A plague grave place.

Green hills reclaimed

by tenement heirs,

the factory girls of

Jacobs and Avon.

5

A hermitage of women live near

Rosary Bead lakes

A pastoral, prolapsed land.

It’s said they have wings

but fly only at night,

lifting off like violet zephyrs.

6

In the Bone Yard

we are our magic selves

among the noise of sermons.

Casting a gauze veil

over the bride of the moon.

How much of our bones

are rock, crystal, sediment.

Nacre in the marrow

holy mother of pearl.

The sacred dust of rocks.

The sea arpeggiates,

pawing at the hem of a wave

you know you want to…

7 The Great Wall of Silence

Audre Lorde wrote

your silence will not protect you.

Every time a mouth snaps shut

— a purse clasp decision,

solidarity evaporates.

Words as immurement.

8 Niobe Basin and the Channel of Tears

You have your mother’s bitter waters,

your mother’s hidden depths,

who avoided a bell-jar landing.

Washed away her anger,

the anchor of disappointment,

turning the linen pink with blood.

They would open us up (if we let them)

Snuffling like pigs in the troughs of our wombs -–

If we let them.

9

On Uaigneach Island a grand ballroom

oozes marble. There’s monkeys on cornices,

gilt-faced tigers, pale girls on plinths

taking orders, fetching drinks.

Waiting like the Galligende

to turn into bears and lionesses

when the night empties out,

restless like Io,

white-flanked and

tormented by a gadfly.

10

Terra Incognita is a place of two lakes

Mater, Pater, bodies of water

I came from theirs,

I came from the silt and knapweed

bed of marriage.

Wives among weeds and pike,

the lake night-mirrored, hiding Ophelias.

11

In the waters of Sentence Strait,

a dervish of waves

dump foam on deck.

Madness spewed from the depths.

Save Our Souls

as stars replicate,

watermarks of light.

Before a fuchsia dawn,

stained yellow-orange;

iodine on pre-surgery skin.

12 Sinners Cove /The Green Island

There is no true north in

the Eye of a Needle,

the compass truth of hidden things.

Be like spears, a goddess told us.

Or the Two of Swords

blindfold and balancing

in front of an archipelago.

Silly Isle Viral Isle

Utopia Heterotopia

Myopia Dystopia

Hysteria Amnesia

Melancholia Oogonia

Colonia Gordonia

The Isle of Shits

The Dreamery.

Forget Ptolemy or Mercator,

ask Mary Ann Rocque or

Joyce Kozloff — who makes the map?

The Raspberry girls long to

escape octopus greetings in

The Ballroom of Romance.

Outside up against a wall,

tongues hot,

breath pluming in iced air,

slick Arctic skin.

A glacier breaks off in the night.

Turn from things glimpsed through

portholes.

Windows as eyes

as nipples

as cunt.

13 Bloody Foreland

Is shingled with witches’ teats

lime rockpools slimed endometrium

on an island where it

rains only blood.

14 Swamp of Transgression

I don a mantellum as big as the sky,

like Mary or Brigid, the shepardesses

of Sundays Well.

A grand oak at the entrance,

each veined leaf, a leaflet.

A minor manifesto.

15

In the Wood of Twisted Desires,

I plant seeds.

Girls as saplings.

Women are dendrochronologists.

A chlorophyll chorus.

16

In Little Ireland,

there are sermons said by pillars,

words in dark green shades

vowels of olive bile.

And afterwards, there is silence

as fear is pushed down throats.

Mouths ferrous, cut lips

all metal, among

copper-domed churches

basted in Verdigris.

17

The Furies

The Goosegirls

The Skate-girls,

The Ray-girls,

The Hake-girls barnacled

to the land

limpeted by laws.

Instead of a ghost town —

the echo of how a place used to be —

Banshee villages are filled with

the sound of women wailing;

not as augury, but for

all they’ve lost.

Swallowing history,

Learning to be what they’re not.

18

At the Hound and Harlot Inn,

we talk loudly about the law.

Our mouths stained purple,

and we drank until our lips

were an advent shade rejecting

the holy spirit.

In the snug of tobacco-yellowed walls,

we opened our grape mouths,

our burgundy mouths,

our Eve-of-the-vine mouths

saying no, no, we will not.

19

In Coventown we burn it all down

and chant until dawn

with

nostrils full of soot, our hearts

already blackened before

flames lick our breasts.

Soon the sun appears,

unfolding long arms of heat

The quartz in the path

Pixelates, all flirtatious.

20

The Three Marys in Pemphredo Lane

started a petition;

Grey Sisters with a shared tooth and eye,

Cyclops triplets taking on oligarchs.

Da svidaniya Vlad, with your Lenin-waxed lies.

Formaldehyde views

All putrification.

Tell the Raspberry girls,

who know all about rot

and Capitalism.

21

From Slutside to Cuntside

we march with our banners

and pink lozenge wombs.

Keep step with bog women,

long sacrificed and

clawing from the earth

through the whistling grass

Here we are to remake ourselves,

To say never again,

Never.

22

The women tell stories of white things:

Autocrat wimples over

soured-lemon hearts.

Bridal veils that could have

kept them out of here.

A tundra of sheets

washed in shifts.

Pre-carbolic skin,

Lay on linen where once,

you felt safe — or desired.

23 The Winds

They told me to wind down,

devolumise myself,

be less blustery

Quit yer monologuing

But they kept on speaking,

tchk, tchk, tchk,

a click-track of dismissal.

The sound bled through breeze blocks

Menstrual notes of birth and confession.

You could almost hear the tears in the wall.

Or the sound of a voice, shouting:

“God doesn’t want you… You’re dirt.”

In the Fields of Salome,

women work the soil.

Raspberry, Strawberry, Blackcurrant girls,

With curved spines like scimitars.

In the laundry, the unwedlocked, padlocked

scrubbing floors post-birth

in smocks,

a lacunae of stitches.

24 Constellations

White bones of stars

light the path,

Bulbs strung like a ship’s rope.

The starry plough needling the land,

looping, looping through

all of those pasts.

We move past erasure,

fabrication

A Scold’s Bridle of

locked documents.

In the Imaginal Forest,

gather paper from

witch-armed trees.

We root ourselves

to fill up cellulose pages,

with an eternal genealogy.

We keep writing

our histories

in contour lines.

Come closer,

I want to tell you:

You are the map.

We are the map.

Gaping mouth’d ...

On the Politics of the Body in the Work of Aideen Barry and Alice Maher

For she was convinced of the plurality of the self ...1

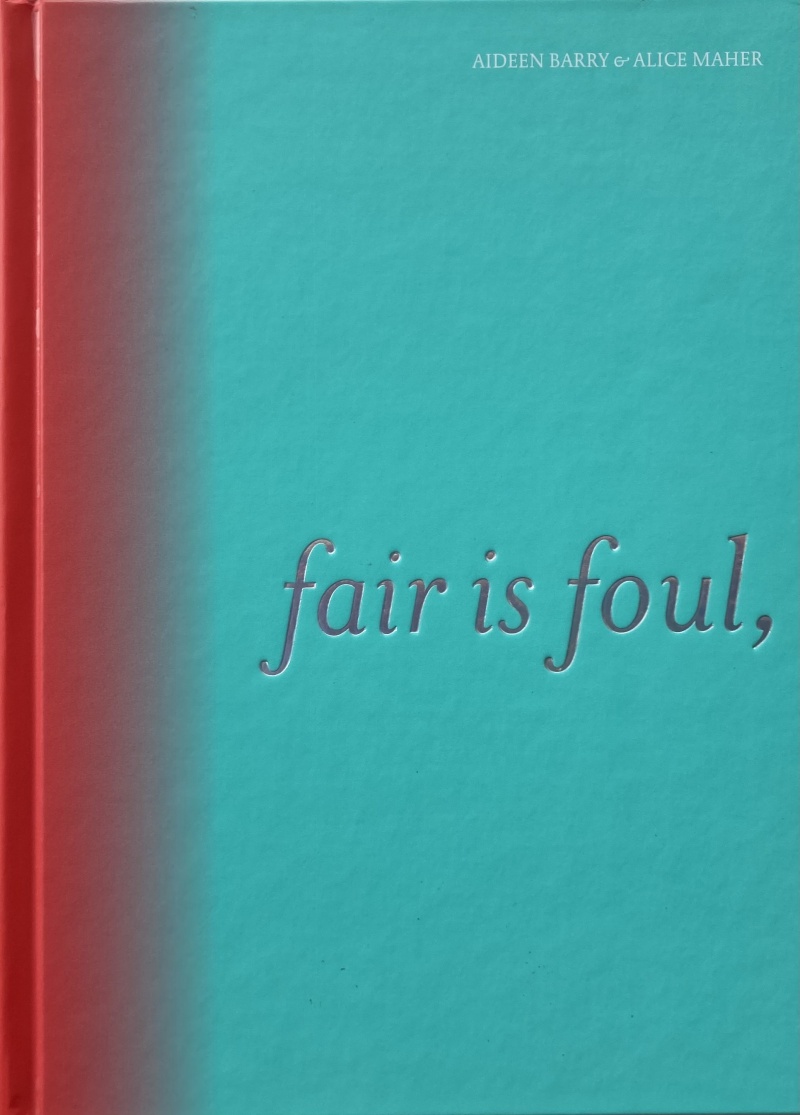

The title of this exhibition is taken from the opening chant spoken by the three witches in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth: ‘Fair is foul, and foul is fair, hover through the fog and filthy air.’2 Inciting the audience to consider that the dramatic events which are about to unfold do not convey the

reality that lurks ominously beneath the surface, the words of the three witches point to the ineluctable truism that fog and filth are present in that which is most fair and, conversely, beauty can be found in what is considered most foul. It is fitting that the words spoken by the witches or weird sisters from Macbeth should set the literary and syntactical mise en scène for this exhibition of work by Aideen Barry and Alice Maher as, over time, the work of both these artists has contained the paradox the witches’ words speak. Barry’s work moves between a luscious, elegiac Gothic aesthetic and unsettling tragicomedy in her performative films by way of the prosthetic extensions and automated mechanical devices she deploys to disturb discrete divisions between the human and what is other to the human, this otherness becoming an uncanny perturbation installed within the self. Hybridity, mutation, metamorphosis and transformation are the keystones for Maher’s artistic oeuvre in which the body is always placed center stage. In Maher’s work the body is a repository for secret, arcane or unsymbolized knowledge and experience, but the body is also the conduit by which such knowledge and experience may yet be issued forth into some new, unanticipated form of symbolization. As the witches incantations evoke witching time as a temporal, topsy-turvy opportunity for ‘hurly-burly ... turmoil, tumult, insurrection and rebellion’, so the work of these two artists agitate canonic historical narratives and visual histories to provoke reflection on the multifarious ways in which women’s knowledge and experience has been omitted from the art history canon: their voices silenced, their laboring bodies obfuscated and refused, their experience expunged from the possibility of intergenerational knowledge exchange.3

As Silvia Federici reminds us, whilst the witch has long standing associations with the heretic, the ‘most important difference between heresy and witchcraft is that witchcraft was

considered a female crime’.4 By way of embodied, intuitive, mantic, somatic and sensorial spellbinding enchantments and incantations, the witch insists that experience and knowledge from the side of the feminine shall not be evacuated from our collective social imaginaries; she literally embodies the subversive spirit of rebellion. A call to arms, to reclaim and resituate lost, fractured or silenced knowledge resonates in Barry and Maher’s work. Like the curse of the heretic or the chant of the witch, it is as an aesthetic insurrection that echoes betwixt and between time as an extended howl or perhaps even a hex. The works on show in Fair is Foul, and Foul is Fair emerge from the bodies of the artists to solicit a somatic encounter, inviting the viewer as a participant to

enter the matrix of corporeal co-vexation. Fomenting and gleaning vexations between the corporeal and cerebral, the material and immaterial, the human and inhuman, the human and its animal familiar, Barry and Maher’s work suggests that whilst the fair is always already in the foul and the foul is always already in the fair, in truth, the foul may be fairer for those whose senses are attuned to that which is most beautiful in what is perceived by others to be most grotesque.

Sometimes the earth may give a jerk, when all the creatures communicate; there may be a hint of cows the bleat of a January lamb the birth of another unwanted baby

the death of a girl and her child.5

In 1983 Article 40.3.3, otherwise known as the 8th Amendment, was inserted into the Constitution of Ireland (Bunreacht na hÉireann).6 Effectively refusing access to abortion unless there was a direct threat to a woman’s life during pregnancy, the 8th Amendment cleaved a traumatic wound through the subjectivity of the citizens of Ireland, impacting profoundly upon women’s health, pregnant people’s reproductive choices and individual human rights. Following years of activism and political lobbying for constitutional change, a referendum to repeal the 8th Amendment from the Irish Constitution was held on Friday 25th May. 2018.7 Whilst the result of the 2018 referendum was met with euphoria by those in favor of repealing the 8th Amendment out of the Constitution, those grassroots campaigners who had ceaselessly campaigned for a “Yes” vote over many years were exhausted and brutalized by the campaign. The work by these two artists that is on show in Fair is Foul, and Foul is Fair was conceived, produced and executed in the traumatic shadow and the traumatizing aftermath of the Repeal movement. This was a time during which thousands upon thousands of pregnant people crossed the Irish sea alone to seek the abortion care their own country denied them, a time when so many girls and women died as a result of the violence the 8th Amendment had wrought on their bodies: the fragment from the poem above keeps one such young girl, Ann Lovett, alive in our collective memory. As the witch serves as a placeholder for the history of women’s subjugation, so Barry and Maher’s artworks materialize the her-say in heresy by manifesting a particularly feminine desire for constitutional reform with the body situated as an insistent, political site of revolt and resistance. Surfacing the effects and affects the 8th Amendment has visited upon the exhausted and brutalized body, in their work the female corpus is also ever

excessive and resilient, yet bound to what Griselda Pollock has termed traumatic ‘after-affects’. Pollock argues that:

.

... the social and imaginative processes of gendering femininity are themselves traumatic within the longue durée of phallocentric culture. Paradoxically this disqualifies women’s experience from being considered

traumatic. Trauma is considered the exceptional event. But many feminists will argue that existence “in the feminine”, the world that women inhabit, is itself regularly traumatizing in general and certain excessive acts of violence and violation ... are embedded tropes if not founding mythos of phallocentric culture.8

In this explication, the traumatic gendering of femininity within a phallic, patriarchal culture is understood to engender further traumatizing after-affects which signal the ‘temporal displacement of trauma, perpetually present, yet absented from memory that bequeaths unbound affects for later events’.9 To elaborate on this theory, Pollock recounts her experience of encounter with a

statue entitled Apollo and Daphne which was carved by Gian Lorenzo Bernini between 1622 and 1625 and details the myth of the nymph Daphne and the god Apollo who, overcome with the desire to possess the beautiful maiden, pursued her against her wishes. Depicting the resisting nymph as she pleads for release from her pursuer’s touch, the moment captured in the sculpture is of Daphne’s imminent rape, which is forestalled as her lower body transforms from soft, pressed flesh into cold, inanimate tree bark whilst a gaping, gasping “O” blossoms on the mouth of the terrified woman. Pollock is transfixed by the open mouth of Daphne in the process of arboreal metaphorphosis and asks ‘Is this dark hole the void of trauma? Whose? Cultures?’10

Fig. 1 Daphne and Apollo (detail), Gian Lorenzo Bernini, 1622-5

I’ve been trying to show you over, and over Look at these, my child-bearing hips Look at these, my ruby red ruby lips

Look at these my work strong arms and You’ve got to see my bottle full of charm I lay it all at your feet You turn around and say back to back to me, “he said” Sheela-na-gig, Sheela-na-gig You exhibitionist Sheela-na-gig, Sheela-na-gig

You exhibitionist.11

I take the gaping and gasping mouth of Daphne as a symbolic codex by which to approach the work of Barry and Maher exhibited in this installation. Daphne’s prophetic “O” reverberates through the process of our culture; her cavernous gaping and gasping mouth ripples across and through our history and the aesthetic time of art history to signal the violences that have been heaped upon the female body across generations. But in Barry and Maher’s work we are reminded that the voice that issues from the female mouth is a mythopoetic signifier that heralds the capacity held within the body to find new forms of affective, aesthetic symbolization to resist the technologies of torture that have sought to restrain it. For the female voice silenced is yet everywhere present in the work of these two artists.

Maher refers to her Vox Materia bronze sculptures cast from wax and displayed as objects as “like a language”; a language that is “squeezed out”, ‘pressed out, spat out, shat out, pushed out, bled out’ and “created under pressure” in processes akin to the acts of defecation or even birthing.12 The sculptures and prints on display in this exhibition are material manifestations of the absent, missing, or lost female voice which suggest both ‘the materiality of the voice and the voice materialized, or rendered into material’ and act as a ‘material expression of the missing or absent voice that arose from the initial pictorial recording’ of the artists own body captured during various movements.13 This creation of a new language merging from the body of the artist and rendered into form is a material link to the initial inspiration for these works: a stone carving of a mermaid the artist encountered on a trip to Kilcooley Abbey in Co. Tipperary. With the advent of this loss of speech we are reminded that the tongues of women, which issue from their open mouths to elicit speech, ‘have been historically associated with ‘curses and spells, the central

activity of witches’.14 Which is why Hans Christian Anderson’s Little Mermaid has her tongue cut from her mouth. To grow legs and live on the land with her beloved, the Little Mermaid must first sacrifice her voice. But, as Adriana Cavarero, notes from the etymology of the Latin vox, ‘the first meaning of vocare is “to call” or “to invoke”. Before making itself speech, the voice is an invocation that is addressed to the other and that entrusts itself to an ear that receives it.’15 As Maher’s work has circled around themes of otherness, becoming, change, transformation, metamorphosis and shapeshifting, these fair-foul exhilarating shapes arrive from the capacities of the artist’s own body: it is the creation of a unique signature language, a materialized lexicon of utterances which

the artist wraps around our eyes, connects to our ears, in a new form of symbolization that makes manifest the previously unutterable. The gaping and gasping mouth of Daphne now speaks.

Barry’s films gesture inexorably towards the myriad ways in which feminine subjectivity is rendered both uncanny and monstrous, hysterical yet prodigious within a signifying economy that singularly valorizes the labor of men. Her time intensive performative films showcase the female subject as a seething, fantastical and phantasmatic Colossus, capable of inhuman feats of feminine domestic perfection. Snaking, Medusa-like prostheses emerge from the artists luxuriant, inky octopus tresses to hoover the house and trim the lawn. Quotidian, everyday domestic devices acquire miraculous animating powers. The artist herself appears, part-Stepford Wife, part-cyborg superhero, part-beleaguered housewife, part-femme fatale temptress, part-machine, herself always in the process of becoming with her mechanical familars which stage a talismanic, almost juju like

presence in her performances. In Enshrined (2016), the complex imbrication of the over- production of female labor meets its nemesis in conjugation with the particular kind of laboring practice that is maternal reproduction. The artist sits at a desk furiously tapping away at a laptop whilst teetering, ever increasing stacks of paper mount either side of her; the stacks of paper are like intrusive bookends holding unruly books together, they are also the pillars of capital which wreak untold havoc upon the female laboring body. Federici draws our attention to the implicit relationship between capital accumulation and alienation from one’s labour by highlighting the manner in which the structures of capitalism systematically reshape and reproduce the labouring subject to conform with its own proprietorial ends.

To this history of female labour, Federici adds the ways in which women have been

wrenched from control over their own reproduction, how they have been forced to procreate

against their will, and how they have ‘

experienced an alienation from their bodies, their “labor”, and even their children’ in a manner that is ‘deeper than that experienced by any other workers’.16

Enshrined evidences this tension between work undertaken for pay and the unpaid work of gestation, labour, birthing and childcare. As the artist sits frantically typing, her body produces a spontaneous pregnancy. With no time to gestate the pregnancy, it is produced as a fully formed egg which is then birthed through the artists open mouth which acts as a stand-in for the maternal birth canal, but which also connects us back to Daphne’s lips opened in the “O” of surprise and panic. The eggs that are hastily deposited onto the work desk fall carelessly to the floor where an untended child makes creative patterns from the gooey mixture of yolk and shell. If ever there was a potent and pathos laden metaphor for the creative work of the artist and mother, this is it. In this way, the egg becomes the symbolic placeholder for the impossible production of femininity, maternity and artistic creativity in late modern capitalist society for the egg or ovum holds to it, as the Surrealist artist Leonora Carrington noted, ‘the macrocosm and the microcosm, the dividing line between the Big and the Small which makes it impossible to see the whole.’17

The voice foreclosed in the marble luminescence of Daphne’s open mouth that I trace through the works of Maher and Barry inevitably returns me to that circular threshold we approach and pass through in the event of our birthing, to the guttural cries that have ushered forth from the mouths of women through millennia in the act of childbirthing, to the first cry of

the infant as it is evacuated from the maternal womb and takes its first breath, as well as the corpse that takes its last. All these phases of gestation birthing, living and dying are evoked by the ancient figure of the Sheela-na-Gig.18 Just as the fair maiden Daphne’s gaping mouth captures the circle of life and death in a gasp that is emitted at the precise moment her breathing body turns to a breathless wooden stump, so Sheela the hag exposes her open gaping vulva as a reminder of the portals we passage through in our journey through life to death.

Fig. 2 Sheela-na-Gig, British Museum

Ireland is an ancient landscape, riddled with sites of ritualistic significance such as passage tombs and underground chambers. Often one enters these spaces by crossing a portal or a threshold which gapes like a starling “O”, to step into a darkened space carved by stone or dissolved from rock. In one such space, the feathering lines and marks on the limestone encasing the chamber are reminiscent of the fleshy tissue-like texture of a vulva or the interior holding space of the womb. Sometimes, deep in the belly of the earth, a swell of thunder claps, resonating through the chamber like a birthing pain or the mother’s voice heard, indistinct, as though from a far. At such times, the chants of those witches who were thought to ‘send raine, haile, tempests, thunder, lightening’, are never far away.19 Here, in the vulva of Sheela the hag, we are connected with the silenced voice of Daphne and to the three-as-one goddess of maiden/mother/crone whose voice erupts in an unapologetic roar that breaches the chronological linearity of historical time to enfold

all time into our time.

Such affective encounters with ritualistic sites of profound significance are lightening rods

which return me to the work of Barry and Maher on show for the occasion of Fair is Foul, and Foul is Fair: an exhibition which provides symbologenic conductors for the ‘history of the body’ which is ‘the history of human beings’.20 Federici argues that there is no cultural or disciplinary practice in the history of human civilization that has ‘not first been applied to the body’.21 Yet, it is by way of an appeal to the body as a ‘ground of resistance’ containing the ‘power to act, to transform itself

and the world’ that the body can be re-theorised as ‘a natural limit’ to such exploitation.22 Through their strategic deployment of affective imagery, forms, materials and lines, Barry and Maher create healing routes to stich the soma back into the psyche so as to give voice to those histories of the female body that have been silenced, unuttered. Cavarero observes, that recuperating the subversive power of the voice in emergence from the body is necessary to radically rethink the connection between speech and politics. This necessity, she argues, does not feminize politics. Rather, in tracing speech back to its ‘vocalic roots’ we extricate it from the ‘perverse binary economy that separates’ the voice that emerges from the body and that is rent from speech and from semantics, so as to recuperate the voice as an ‘obligatory strategic gesture’.23 From the witches chant, to the gaping and gasping mouth of Daphne, to the enigmatic whorls and fissures that appear in Maher’s prints and sculptural objects, to the alarming cavernous mouths of Barry’s

Medusaesque hoover extensions and the incessant eggs that appear from her mechanical opening and closing mouth, the artistic voice in emergence from the body is everywhere in these works by Maher and Barry. These artworks produce a re-corporealized form of speech that works towards a politics of the somatic and they may provide us with the very tools we need to stage our resistance to the various forms of biopower which continue to seek control over our laboring bodies to this very day. We must, therefore, watch and listen.

Our bodies have reasons that we need to learn, rediscover, reinvent. We need to listen to the language and rhythms of the natural world as the path to the health and healing of the earth. Since the power to be affected and to affect, to be moved and move, a capacity which is indestructible, exhausted only with death, is constitutive of the body, there is an immanent politics residing in it: the capacity to transform itself, others, and change the world.24

1 Mariner Warner, ‘Introduction’ in Leonora Carrington, Down Below. New York: New York Review of Books, 2017, p. xxvii.

2 William Shakespeare, Macbeth, Act I, Scene 1.

3 A. R. Braunmuller, ‘Introduction’, Macbeth, William Shakespeare. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 102.

4 Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, 2004, p. 179.

5 Leland Bardwell, ‘The Flight’, The White Beach: New and Selected Poems 1960-1998. Cliffs of Moher: Salmon Publishing, 1998.

6 Generally referred to as the 8th amendment, Article 40.3.3 reads as follows: ‘The state acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right’.

8 Griselda Pollock, After-affects/After-Images: Trauma and Aesthetic Transformation in the Virtual Feminist Museum. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013, p. 1.

9 ibid, p. xxxx.

10 ibid, p. 49.

11 P. J. Harvey, ‘Sheela-Na-Gig’ (lyrics), Dry. Too Pure, 1992.

12 Tina Kinsella, ‘Corporeal Matters’, VAI News Sheet 3, 2018, p. 21.

13 ibid.

14 Warner, Signs and Wonders: Essays on Literature and Culture. London: Vintage, 2003, p. 61

15 Adriana Cavarero, For More Than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005, p.169.

16 Federici, 2004, p. 91

17 Leonora Carrington, Down Below. New York: New York Review of Books, 2017, p. 19.

18 Sheela-na-Gigs are carving of naked women displaying an exaggerated vulva. Whilst these figurative carvings are found across northern Europe, Ireland has the greatest concentration of them. The original meaning these enigmatic figures convey is lost in the mists of time, but various hypotheses have suggested the Sheela is a fertility figure, the remnants of a pagan goddess, a warning against lust or a figure of feminine empowerment.

19 A. R. Braunmuller, 1997, p. 102.

20 Silvia Federici, ‘In Praise of the Dancing Body’, Visuel Arkivering 11. Published in relation to Motherniziing ANA: Who Cares for the Future? Astrid Noaks Atelier and The Mothernists II: Who Cares for the 21st Century? Danske Kunstakademi, 2017, p. 25.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Cavarero, 2004, p. 207.

24 Federici, 2017, p. 29.

Nine Silences

Prelude: On the Shared Traits of Mermaids

Physical:

Breasts: exposed or scallop-shelled. Below the navel, skin turns tail. Long hair (often fair). Pale.

Possessions:

Always an enchanted cap/cape/cochaillín – even when stolen, this object remains her belonging, never his. Mirror. Comb. Manacle. Wedding ring. On occasion, a clutch purse may be seen, or even a pocket-watch (concealed).

Disposition:

Chronic gloom. Mute. Silence aside – sporadic gasps, sometimes heard to laugh in the bath. Erratic when trapped. Given to long sighs. Elevated risk of suicide. Characteristic long gaze; captivated by water, by falling, by rain.

Footnote 1:

Modern cases are rare. One condition, known as Sirenomelia, manifests as fused fibulae, with multiple co-morbidities, and low life expectancy.

Footnote 2:

Whether taken for myth, saint, or human being, in time, she will always turns back to water. No happy ever after. Never.

(Be)longings

For you, a comb is a silver loom, a mirror a moon,

a man’s hand, a harpoon. In truth, these heirlooms

were left to you by women who knew how to find such

tools and put them to use, no matter how blunt or crude.

They knew that once he steals your cochaillín,

you will never leave. Soon, you’ll see how nails

print five moons in the skin under a sleeve. Soundless,

the bevelled edge, where his mirror always held

a prism captive, slant spectrum of gold, violet,

crimson split: an omen, this. Only now do you see it –

but hush, girl, hush – you are not the first to touch

your skin against such implements and call it love.

Desire finds every woman among us, the way

a rear-view mirror unwinds a day in grey glare.

You may swerve away, but you’ll still feel it there,

for free is a fairy-tale, a lie told by the road behind.

What really propels your life, if not this sight,

revealed in the mirror as you drive? It grows late,

and you turn home again, driven through the dark

by the weight of a silver tail: muscular, silent, scaled.

Another Orgasm against a Wall

Hold my throat and my silence sings

a wordless hymn – to belt buckle click,

to fingers and spit, to skin and brick –

and though it is too dark to see,

I feel my breath move inside

the wall, away from me.

Each sigh of mine turns firm

in there, beyond layers

of plaster and horsehair;

each gasp turns

gold, wedged tight

between old stones.

*

In Fermoy, an English boy

met a bullet in the street.

His last breath bled into gravel,

setting soldiers roaring up from his garrison,

smashing every merchant’s glass,

swearing over armfuls of wares.

Each object floated for one thrown moment,

then slipped in to the river's swift skin –

stockings, rings, cufflinks, all swept away –

all except the clockmaker’s display.

His soft velvet tray spent a second

held between belly and bridge,

where the sun’s rays lit each pocket-chain

and case, warming every patient face.

Sudden, the plummet into the river’s

thrust and shove, the rough tug

through that tumbling suck, to become

wedged tight in stones and dirt.

Stuck. No chime from murk,

no tick in silt; between those stones,

their hours stilled.

A trout’s belly pays no heed

to intricacies of hairsprings

or escapement wheels;

the river’s silver flow cannot

know the convolutions of anchor

or arbour, bezel or bow.

No soul walking home from the pub

alone would go to check the hour

in the Blackwater’s tremble-throat. No,

no-one remembered them, not their hands

or faces, not the slender apertures

that once moved to the phases of the moon.

*

I do. I think of them

when my breast is pressed

against a wall again.

I, too, sing nocturnes

of silence, of moon and skin,

and in that hymn,

my breath spills

gold between old stones

again. Again.

Rondelet for a Mermaid in her Third Decade

She stares at rain,

how it falls, fails, then falls away.

She stares at rain,

and her gaze strains the window pane,

all the falling drops of her days.

Pale castaway – she sways, she sways,

she stares at rain.

A Man’s Hand, A Harpoon

Skull of a young seagull,

gift of sea to sand, lifted

to us in ripple and dulse

to fetch up in my lover’s hand –

and that hand, it always was a map,

steady, lined, calm, it steered me

from days of lull and lapse,

and set me gasping in his land.

It led me to bed, it held, it grasped,

all week, I worked for that hand,

so Sundays, it led me along a dune path

and all the way down to the strand.

It showed me the ocean, let me walk

the sand, but never enter that salted fizz.

So gentle the grasp of his hand,

so light, the restraint from such whims.

Under sugar kelp and barnacles

it lay, the skull he glimpsed –

gift of Atlantic, toothpick-thin,

it seemed a pretty ornament to him.

To me, it sang loud of soar and sound,

of screech, sky-spin, storm-tilt,

of heights over ocean and ground,

of catapult, plummet and spill.

That hand lifted the skull as an offering,

if it was his to give – a gift, a present,

akin to a wedding ring. I grimaced

the quiet sting of sea-wind.

On his shelf, it will sit, brittle relic

of a gull who soared high and swam,

stretched to me with a kiss,

meekly lifted from his palm –

but first, drench her, drench her,

feather and flesh her, fly her

back into the sky, let her breathe

a last moment of pleasure,

for in living with him,

her flight dies. Someday,

when the ash of his hand

has left mine, I’ll lift

this small skull and sing:

O map, o bone, o future

alone, o waves, o me, o him,

and maybe I’ll carry her

back to the ocean, return

her to ripple and dulse,

maybe I’ll swim in myself

to set her floating,

and hear gulls’ shrieks

slow

with my

pulse.

The Saint of Peacock Lane

How quick she slipped from the womb, this little one lifted into our universe of sisters. Cold, the room, blessed by silverish moon. Unbroken, the bubble, for she came borne on her own ocean. Unspoken, her name. Unspoken, her tail. In the caul, I saw her swim, little castaway. Her mother turned her face away; pity her grimace in silence, thin slip of a thing, skinny-hipped, brazen-lipped. Not once did she meet our gaze, not when her hair was clipped, not even when Mother gripped her by the chin. The baby’s eyes opened, I swear, I saw her squirm, swimming in there, but once that sac was slit, she turned. Still. No cry. Into silence, the child that was her mother howled instead; oh, she wept and bled. I laid clean towels and held her head. I lied: God's mercy that a baby like that be born dead. She gripped my wrist, she hissed: take her away take her away take her away away away. I did. Alone, I touched her tail, I saw the haloes in her irises spooling blue. So blue – when I saw them, I knew. She was Truth. I found her a hollow borrowed from earth, laid her in a pillowslip, light as a bird, I threw her fistfuls of night bluebells and honeysuckle, dark dirt, and a whisper: Miracle. Three weeks later, an uncle gripped her mother by the elbow, led her away, away. I wanted to say: Wait. Every day of my life I will stay at this laundry to watch over her. Even if I didn’t say it aloud, it’s true, I knew I’d mind her, and I do. Every day, I scoop the palest pebbles from gravel greys, so on Sundays I can spill them on her grave. I’ll make her blessed shape shine brightly through this place. When I’m gone, brambles will tremble here, lifting blackberries over her small face, and still, on the dark earth, the mark I make will remain. Shape of a salmon tail. Sacred. Pale.

A Split Second of Her Eighth Decade

- after ‘Cell (Eyes and Mirrors)’ by Louise Bourgeois

In the kitchen, a sink of dishes

and in it, her fingers seem so different

submerged, scalding pink, the cross-crissed

mesh of suds and self – how sharp, its sting.

Again, nightfall, night fell, and every night,

the same ritual again, the same assortment

of dreadful vessels. In the draining day, no, no,

I mean to say, on the draining tray, her own

gaze gleams, see? See the twin dark marbles

of her eyes captivated, capsized,

reflected in each spoon and knife. And night,

o moonless, steadfast night, now, it arrives,

and casts its spell in the garden outside,

turning the window into a dark mirror

and from its innards, her face is floating up

again, o, omen. O woman who looms back

from vast black once more, older though,

and flinching, sore, with arthritic fingers,

and distorted toes. She aches, and night makes

of the kitchen window a lake, where she is

watching her shape lifted from darkness

again, hoodless, still, lips pinched, mute,

alone, reflecting on all that may never be

saved from steel and stone.

Deilfín

delphinedelphinedelphine on steamed-up mirrors,

always in joined-up finger-writing.

- Amy Key

Conceived in sea, of brine and seed,

she chose me, my Deilfín.

Her birth was tear, bleed, bent,

creep and crept and forceps

wrench. Men shook their heads:

Sirenomelia, they said, extremely rare.

Precious, then, I say.

Embryonic, antique, the genetic

script written before her fingers

first twitched. I chose a name

carefully for my little dolphin,

my Deilfín.

I conjure her new, now,

gurgling clues, pram-flat, rapt

in the blankets I clickclacked

while she swam my belly-blue.

Deilfín, Deilfín, I crooned

for you, and again

the kittens lost their mittens,

and again I caught a fish alive,

and all the while, your infant fists

were opening, opening to show

the shapes on your palms,

almost waves. Almost waves.

I saved your file, fastened still

in eight slack elastics. How it followed

us though surgical lists and hospitals,

gathering scribbles – Congenital –

Kidneys – Surgeries – Morphine –

Transplant – Autism – Mutism – and –

and – and they say mute, but you could

laugh; I heard you often in the bath, though

throwing open the door turned you brazen,

all eyes back. Mute? I knew your scream.

Don't ask. I’m no saint.

Too often, I blazed cantankerous, I raged.

Everywhere you went, you left a stream

of stickers, sheaves of queens and fairies,

each pressed, left to set, then spit and split

with such gentleness until only ghost

shapes remained, fixed on the TV, on windows,

on walls, fuzzy, grey, all along the hall

and up the stairs, and when I carried you

to bed, you stroked them, your scales.

How I prayed: Sticker. Stick her. Fix her.

Keep her stuck here with me, my Deilfín,

my little one in her gold pin curls, tiger-stripe

smock, little cap of silver polka-dots.

No. She’s gone. I failed. She went back

to water, her ash lost. Now, she speaks

only when I breathe her name to the

mirror. Deilfín, Deilfín. Where her fingers

once swirled through steam on glass,

now a chorus of voices echoes back.

Escape: A Chorus in Capes

we are leaving our babies

fed and warm in their cots,

we are leaving dark kitchens,

untying apron knots

we are stumbling in nightdresses

through doors left unlocked

we are grasping towards water

past badger and fox

no moon, no, no star

when we wrench off our socks

only darkness so sharp

it fills pockets with rocks

if cloth held us captive

it may free us as well

so we don our dark hoods

leave red footsteps in gravel

we walk into rivers we walk into seas

we walk into lakes we will never speak

icy, the waters

over toe, heel and ankle

numb, the swerve backward

legs and lungs turn untangled

we are swallowed by water

we will never rise

we return through dark borders

leaving dry lives capsized

“What were her wishes?”

– Unknown –

All I ask

is that you scatter that ash fast,

don't hold it close, don't let your teeth gnash,

don't weep, don’t keen. Let go of me.

Please. When the sea swallows me, turn

your back. Let me go, let me fall back,

back, back to the past.

That's all I ask.

At Kilcooley,

he is birthing her from stone,

alone. He coaxes her

by snip-snip-chisel-chip,

as though lifting a body

from slate-grey seas, slow,

o slow, this birthing. He sees her

grow; he sees her grow cold:

the face, the breast, the waist.

He gives her a tail, and a manacle,

raised, then pauses to imagine

the rest. Gifting her a mirror,

he sets a comb in her fingers,

then tilts her gaze over, just a little.

O cold birth, o shiver, he wonders

how long she will linger,

for soon, he knows, he must

leave her, so he lifts her

two fish as grinning

companions, then coaxes

her lips from cold stone,

in silence. He steps aside,

andsmiles. She is finished.

The Fishmonger, The Falling

In the queue, the air was hectic

with the thick stench of fish,

and I always paused for a minute,

stretching a long yawn to mock

the octopus, the crab claws, all

these heaped faces of an ordinary

slaughter. Stupid fish;

they are killed. I live.

I sensed something electric

that morning, in how the new

fishmonger lifted his corpses.

I liked his knife, how it slit

their sides, freeing them

of redness, slime, and tangled

intestine. I thought

of his ribs, how my tongue

might swim those shallows,

and if he was young, younger

than the others, what of it?

I hungered for his breath,

how air from his chest might

live in my mouth a moment.

I watched his hands flip plastic

handles, I watched his dimpled grin.

Yes, I thought, I will take him.

He never saw me approach

(they never did), there,

where fish-guts and blood

slid from apron to gutter,

from culvert to sea churn –

but other eyes saw it all.

Wide, the wakeful gaze

of shark, mackerel, and hake,

every dead eye that knew

my kind as I moved through

that queue, close, closer,

my cold pulses quickening.

I won’t ruin the ending

by saying what became of him,

but I’ll tell you this: it was good,

back then, to learn to ignore

the stench of death, it was

a useful cleverness to carry

into war, the knack of standing

haughty when surrounded

by corpses, to smile despite

the tender slip of organ from knife.

But as I said, this was all before.

Yes, this was before the war.

Female Silence: 9 Types

1. In the eyes of another: Stern. Taciturn. Bitter. Firm.

2. Beyond a window, a face, sink-blurred. Every day, she rubs the same spoons underwater, mouth downturned.

3. A teenager grits her teeth when a stranger sneers: Cheer up love, give us a grin.

4. Tongueless, the laundress draws silence from steam, hauling the wordless heft of scald, scrape, deformity.

5. Examined by soldiers, she won’t speak. Interrogated by more, her curls twist in a stranger’s fist. White, white, her lips clench so tight, until shears give her hair flight.

6. A century of silence, in which little changes. Her granddaughter’s words will be swallowed, still, unspilled.

7. Inheritance: each female syllable is bitten, held imprisoned. Until it isn’t.

8. Silence in brine: saline. The sight of fish tails set for pickling, five in a line.

9. Intersection of time and desire: the sunken clock will swallow its tock-tick only if the river spills its captive. Sacrament.

10. The silence of knives. The kitchen, so quiet. Slice. Slice. Slice. Slice.

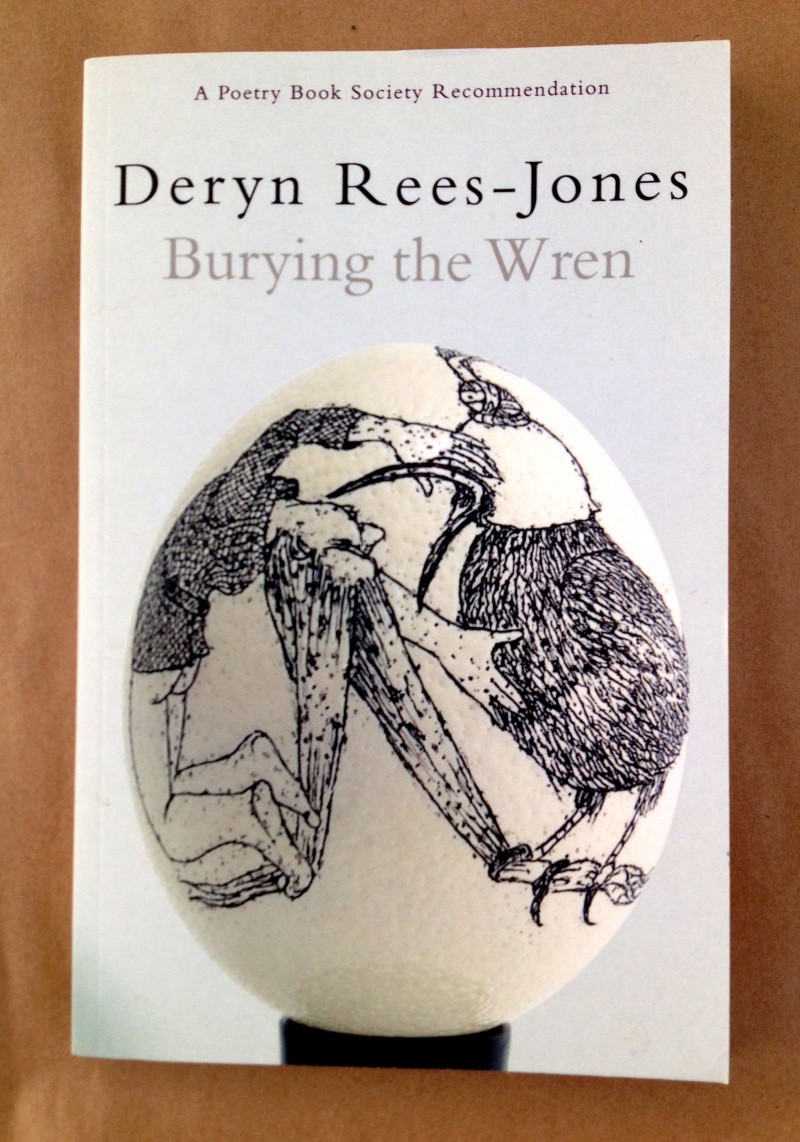

Notes on the Poetry

As a girl growing up in rural Clare, I was very aware of the mermaids in our local folklore. Thanks to seanchaí Eddie Lenihan, I had a strong sense of the Newhall Mermaid in particular. This mermaid was constructed as a female presence both monstrous and powerful, a being who routinely stole from a wealthy landlord, eventually turning a lake red with her blood. In more recent years, I have also admired Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill’s casting of her murúcha in all their post-colonial, existential, and linguistic crises.

On a cold afternoon in Tipperary, a pair of swans flew over the car as Alice and I drove to Kilcooley Abbey. There, a mermaid carved into stone rose under Alice’s hand, a slow birth into paper and charcoal. I carried a rubbing of that mermaid home, and wrote these poems under her silent gaze. The poems gathered here seek to articulate some of the many shades of silence embodied by mermaids, how this myth can allow us a chance to listen closely to other silences, those that make themselves manifest within the female body, and within female consciousness.

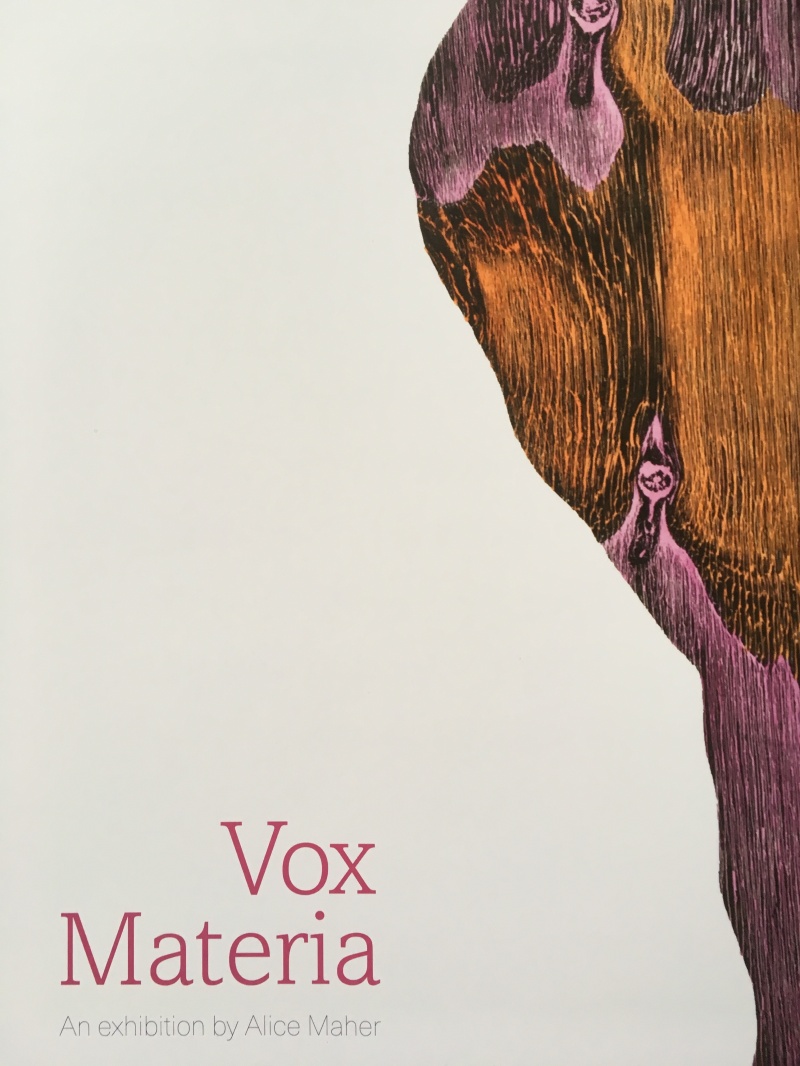

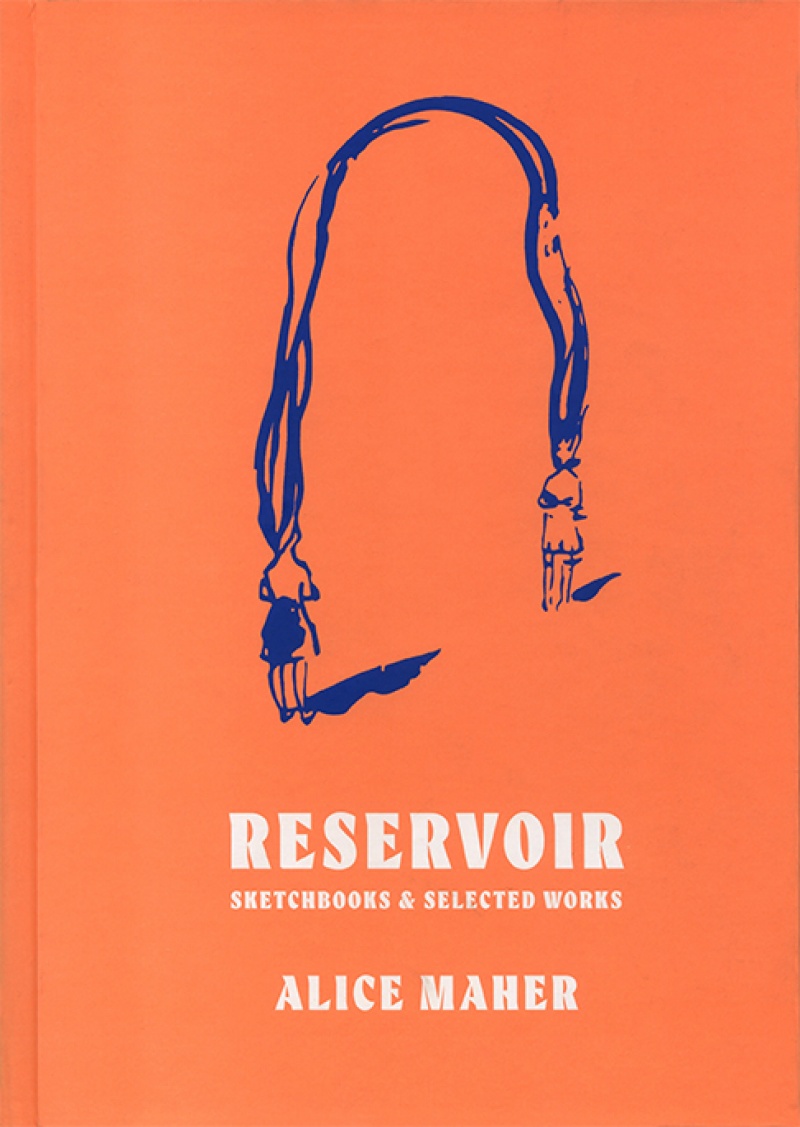

Vox Materia – the substance of a voice, a voice made palpable, tactile, material. The work for this show hinges on a new intervention into the ideas of expression and obstruction that have been central to Maher’s practice. Expression carries within its etymology the idea of something pressed out, under pressure. Pressure and expression are registered here through facture as well as conceptually, through wood relief prints and a suite of small bronze sculptures squeezed from the artist’s fist.

Building on her previous practice of engaging with historical and mythological sources as a starting point for material exploration, Maher began the work for Vox Materia by looking at two sources that can be understood in relation to women’s histories and struggles for equality, making this body of work something connected to both ancient histories and contemporary debates. The first point of reference was the 12th Century carving of a mermaid by an anonymous sculptor, and the second source was the baroque sculpture of Apollo and Daphne (1622-25) by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (figure 1). Maher has long realised the power of narrative to draw in her viewers, having considered the relationship between femininity and myth throughout her career. With her usual attention to those historical characters that bear on our contemporary conversations, the figures of both the mermaid and Bernini’s Daphne, frozen in the moment of transformation, are fecund ones for interpretation, full of mythopoetic potency and violence. However, although these themes are all present, Maher diverges from her previous interventions within narrative to create recalcitrant material objects that remain obdurately unfamiliar.

Mermaid Emerging

‘mermaid emerging’ was the subject line of an e-mail Alice sent to us during the early stages of this project, containing photographs of her making graphite rubbings at Kilcooley Abbey near Thurles, Co. Tipperary. Struck by the figure, Maher produced a rubbing of the relief, creating an indexical trace of the stonework. In the photographs of this process, we see the trace of the mermaid emerging in striating lines, an index of the shallow profile of the original, rendered in negative to reveal a flattened figure with a skull-like, grimacing face (figure 2). Typical of Maher’s interest in complicating representations of femininity in ancient sources and hybrid forms, this mermaid is no temptress. Instead she is pictured as monstrous and restrained, captured by what appears to be a giant manacle around the tail, revealed by the artist’s rubbing.

Designed to keep the curatorial team, based between Cork and London, up to date, the ‘mermaid emerging’ e-mail showed early engagements with site, cultural memory and material trace. In one photograph, the artist has one hand pressed onto the paper and the wall behind it, the other creating the marks that reveal the mermaid’s profile. The nature of this transference is worth considering; not a re-rendering, instead it is an index of the curves of the stonework behind, made possible because the stone is flat enough to facilitate a register of the work. The trace made through the repeated scribble of the artist’s hand translates the hard, cold stone into a more tactile form. The grainy detail demonstrates the inexact nature of the transfer, gaps of white show through where the stone is flat below and the detail of the mermaid is made ethereal by negative image. For final work that so clearly speaks to the body, it is interesting to think of the graphite rubbing in relation to the wood reliefs and bronzes – the material engagement with the cold, hard surface of the stone to record a fictional body so resonant with other meaning. This gives us a way of thinking about these works that develops through process, updating the artist’s on-going engagement with the notion of becoming – the title of her 2012 exhibition hosted by IMMA in Earlsfort Terrace – and inscribing it into the development and evolution of Vox Materia.

The works on show here have not developed directly from the rubbings that Maher made in 2017. Instead, there are two distinct processes at work. The first underlies the strange, creaturely wood relief prints that fill a single wall of the gallery. This new suite of works on paper appears at first like tightly delineated pools, suspended in unrelieved whiteness. Abstract yet insistently physical and densely striated; the forms, overlaid with bright watercolour wash suggest something visceral but not securely human. Exploring shape and gesture through physical movement, the first stage in the process of making these works involved a photographic recording of artist’s active body. Maher – interested in considering the body not as a field of representation but instead as one of experience – began the process physically, moving slowly through contorted positions, focusing on the feeling of stretching and shifting. These are the opposite of posed positions: rather than presenting the body to an outside eye, the camera acts as a partial trace of the artist’s experience of corporeality (figure 3). What emerges are chronophotographic records that show the artist hunched and stretched, the gestures, translated into a series of still images, offering us a fractional record of an internal and individual exploration of the body. Similar to the graphite rubbing, there is a translation here that stands in relation to its original, but alters its meaning, at a remove from the original process and experience, but entirely affected by it. Looking through the resulting images, Maher selected number to transcribe into pencil drawings. For these, she focused on the silhouette rather than the detail, adding another layer of process that obscures the connection to the image of the body and distances itself from the original movement. In their final stage, the pencil drawings were translated to wood relief prints, creating striated and grained silhouettes which were then hand coloured by the artist (figure 4).

The silhouette has been a feature of Maher’s works since 2003, with works such as Poet and Foxtail, followed by her Lectores Mirabiles series for the National Library in 2004 where decorous bodies sprout fantastic, organic appendages, alluding to the

imaginative possibilities liberated by reading, while her 2007 show The Night Garden populated the RHA’s Gallagher Gallery with pullulating crowds of Boschian hybrids. A silhouette compresses a three dimensional form into a flat shadow, unalleviated by detail, floating in an unalleviated sea of background. It’s an abbreviation, an aide de memoire. It is also linked to the very beginning of art history; Pliny the Elder recounted how the daughter of Butades the potter recorded her lover’s profile before he left for war, tracing his shadow cast on the wall in a pencil outline, providing a reminder indexically linked to its original[1]. Against such melancholy beginnings, the origins of the term silhouette are less grand , traced back as it is to the French minister of Finance, Etienne de Silhouette (1709-67), noted for his parsimony in public expenditure[2]. His name was applied to things made cheaply, including inexpensive portraits cut from paper, rather than more elaborate portraits made in oils. Reducing three dimensional objects into flat renderings that elide their detail, the silhouette condenses the subject down to its shadow in a reduction of means and technical acuity, an accessible form of representation. Not quite a folk art, but a hobby of amateurs, use of the silhouette ties in with Maher’s investment in media or materials traditionally unvalorised by art history.

Unlike the traced outline or the shape cut from paper, these silhouettes have been translated into a form of relief print. While woodcuts or woodblock prints are traditionally carved, the composition gouged out of the wooden block or plate and then inked and passed through the press, Maher’s wood reliefs are different, compact yet undulating forms cut in outline from plywood and unrelieved by carved marks. The glitches and whorls of the wood’s surface absorb the ink and are pressed out onto the paper. The marks and patterns don’t immediately register as knots or wood grain however: there is something pelagic about them which evokes pools, eddies and rivulets, or the crenulations of a sandy beach at low tide. Something bodily also; the knots suggestive of eyes or ears of navels; orifices where the body opens out to the world - or even something geological; layers of stratification and sedimentation compressed over millennia. The resultant images are insistently physical but obdurately refuse to cohere. They have been rendered strange in their translation from medium to medium, like a Chinese whisper. The outcome is an insistently flattened image that retains the trace of each layer of this process. Not removed, but reduced, the literal pressure of the press that creates the prints can act as a metaphor for the translation of movement into image, as though the artist’s physical experiments, the drawn mark and the rendering of the three dimensional plates have all been compressed into a condensed and resonant proposition.

This process of translation is also at work in the bronze forms that sit in the centre of the gallery in a large cabinet, long, low and wedge shaped, so that one looks down into it, as if into a pool. Arrayed in this cabinet are twenty-three small, sinuous objects, slickly patinated. These sculptural forms fit in the hand and were first made from wax, squeezed in Maher’s fist, and then dipped again in molten wax to achieve a smooth, slippery finish (figure 5). Each shape then registers the force of her grip, recording the fins and bulges that escape through the gaps in her fist, extruded under pressure. In this way the objects display evidence of the movements and the physical effort that produced them, retaining the memory of her gesture. The process results in simple, primal forms which evoke both sensual pleasure but also a measure of perplexity. As with her 1995 exhibition Familiar, there is a complex dialogue at work between the works on paper and the sculptures. Like the relief prints, these objects also refuse to resolve, or rather, refuse easy identification: they are at once bones or turds, organs or lumps of coral. If we were to pick them up, then would be heavy, smooth and cold; intimate yet leaden and resistant.

In both cases, processes that started out in movement end as determinedly static renderings of abstract shapes: not fleshy or visceral but bodily still. Given the images translation from medium to medium: the photographed body, translated into a hand drawn silhouette, translated again into a shape cut out in wood and then passed through the printing press, the original sense of – or recognition of – the artist’s body is obscured, but a sense of embodiment does remain. These works convey an insistent physicality, yet one seeded with ambiguity and ambivalence. Given this, we might ask what kind of experience of embodiment is being communicated here in the fleshy creases and folds, skewed and compressed limbs that split and intersect. The roseate, mottled bronzes too – small and sleek, summoning touch – are they biomorphic? Organic? This does not seem to do justice to their highly polished surfaces that are smooth and pebble like: looking more like objects found but not fully understood, some archaic projectile perhaps, or some trace of a ritual long since forgotten.

Suggestive as they are of other meanings – something we’ll explore further below – it is important to dwell on the physicality of the works on display here, particularly on their connection to an absent body made manifest through its trace. The index of Maher’s clenching fist in the bronze sculptures and the layers of translation in the wood relief prints from movement to drawing to printing to watercolour, act as residues of the artist’s process, one so closely tied to corporeality. Both sets of work register intangible aspects of the body. In the bronze sculptures we see a record of the force it exerts on the wax form, the effect of muscles contracting, compressing a malleable substance to the point of resistance, ending as a document of movement and resilience, cast in bronze as a permanent memorial to this physical relationship between an artist and her materials. In the works on paper, we see a process of translation that offers an unexpected interpretation of in the internal experience of the body, investigating shape, material and form on the basis on an initial exploration of a physical sensation. Those twists and contortions that the artist first experienced end in an image that renders a view of the strangeness of the body when considered with focused attention.

The hybridity of the images suggest creatures on the boundary between human and animals: as hybrid as mermaids, but less specific, more monstrous, less defined; which derives from that focus on the body as felt. In both the knotted, abstract figuration that emerges, and the lumpen traces of a now absent body, there is a rejection of the conventions of the representations of women, a constantly marked and problematic territory. Through offering a view of the female body as a site of interiority, explored from within rather than from the outside, Maher offers a feminist complication of the initial image of the mermaid. Hybridity becomes not a reference to a strange and threatening mystical creature, one that remains external to our everyday experience, but instead describes an excess that is always within the body, as an always present internal experience where sensation suggests meaning, where the distance between the imagined insides of our bodies – the muscles that flex and stretch, the blood that flows, the synapses that spark – and the outside world that requires translation and interpretation.

That this is both a subjective exploration and a gendered one is important. The practice of writing the body (to paraphrase Hélène Cixous’ famous call to action) is not new amongst feminist practitioners. Artists have been examining ways to re-imagine the body in art since the advent of the feminist art movement in the 1970s, considering how to visually imagine the female body in light of the sexualisation and objectification that have historically accompanied its imaging. Maher’s flattened creaturely forms and petrified lumps can be read within this lineage of art practices, differently inflected as they are by their reference to the ways in which female bodies negotiate space. However, much as this theory has evolved since its first discussions in the 1970s, the female body is no longer imagined as the transhistorical, transcultural phenomenon it was conceived to be in Cixous’ first considerations. Instead, Maher’s works seek not to represent an amorphous female viscerality but instead are specific to her own body as a woman negotiating the at once vexed and yet increasingly optimistic territory of the female body as it is imagined in contemporary Ireland. For exploring this in more detail, it is necessary to turn to the significance of myth in interpreting these images, which we argue, stand not as a transcultural reverberation, but as a set of parables that relate implicitly to our current political landscape.

Myth in 2018

An engagement with mythic femininity was important to Maher’s development of this work, providing a series of conceptual markers through which to frame the project. The mermaid that emerges from beneath Maher’s graphite pencil for example, is one that suggests a female figure made monstrous, imbued with a threatening sexuality. Historically understood, the mermaid is a siren that has lost her voice; in some stories, very violently - her tongue ripped out so that she might be granted human legs - a silenced figure that is at once irresistibly seductive and also a harbinger of disaster. Silencing emerges as an important idea underlying this work, not only in the mermaid’s lost voice, but also in the other important reference point which informs this work, Apollo and Daphne, the sixteenth century sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

Specifically, it was the dark void presented by Daphne’s open mouth, emitting a wordless gasp/scream which stood as the punctum of the work for Maher. Griselda Pollock’s essay on the sculpture draws out its mythopoetic significance: Daphne, fleeing from Apollo’s violent pursuit, calls out to her father, the river god Peneus to save her from her attacker.[3] Bernini’s work famously captures this moment of transformation, as Daphne’s soft, fleshy body petrifies into wood, rough bark and snaking roots. This act of rescue is also an act of violence, the hard bark that protects her naked body from Apollo’s uninvited touch in Bernini’s sculpture also acts to encase her. For Maher, Daphne’s gasping/screaming mouth contained within it the abject reality of this tale. Her focus is not on the beautifully carved marble, but the empty space cut in stone that represents both Daphne’s cry and the last breath expelled from her transforming body.

How to link these coded references to the baroque sculpture and the 12th century mermaid carving? Both derive from myth, and both involve hybrid states, implying or actually depicting the process of transformation. The reference to myth is helpful for thinking further about the relationship between this work and feminist understandings of the body. In Marina Warner’s study on the tropes of popular fairy tale From the Beast to the Blonde she points out that fairy tales such as those by Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Anderson – the Little Mermaid providing a prime example - encrypt procedures of authority from various moments in history, valorising silence as a feminine virtue, and thus encouraging young girls to become passive, silent and obedient.[4] Likewise, when the brothers Grimm collected fairy tales, they tended not to include stories which existed in folklore that featured strong, clever female heroines, and instead gravitated (however consciously is debatable) towards stories with active male protagonists, and passive females.[5] Not only that, but Warner cites Ruth Bottigheimer’s analysis of the speech patterns in the Grimms – as the Grimms published their later editions, the female heroines used less and less words, and the female villains spoke more.[6] Thus, she argues, girls tended to subconsciously receive the message that to be worthy and desirable like the female heroines in the stories, they must be quiet. Myth then stands as a way of thinking about how gendered codes of behaviour and expectation are communicated socially not as ideological assertions that demand particular types of behaviour and forbid others, but instead as universal truths related to long standing historical knowledge. As Griselda Pollock reminds us, ‘myth is [...] at root a fable of the tensions in culture, translating into stories the rules of conduct of a social group or a cultural formation’[7].

However, the ways in which this myth plays out in contemporary culture are not predictable as Ashley King Scheu identifies. In her study of Simone de Beauvoir’s interest in myth in her writings, she points to the ways in which mythological and fantastical renderings of femininity feature in the author’s recollections of her childhood, how, rather than silencing Beauvoir and her sister, instead they would engage with their narratives, ‘[taking] up the well-known stories of martyrs and wicked stepmothers and manipulat[ing] them, recreating their stories just as they pleased.[8] Scheu excerpts Beauvoir’s descriptions of the effects of this: ‘Just when the silence, the shadows, the boredom of the bourgeois buildings invaded the vestibule, I would unleash my fantasies: we would sometimes bring them into being […] enthusiastically supported by gestures and words, and sometimes, as we caught each other in our spell, we would succeed in taking flight from this world, up to that moment when an imperious voice would call us back to reality’[9] Even patriarchal myths therefore, though unquestionably formative, are not necessarily determining: their effects are intangible and their results unexpected. So it is for Maher and for women who were, like her, raised in 1960s and ‘70s Ireland. Rejecting the patriarchal narratives of conservative Catholicism and insisting on the importance of women’s voices, Maher was one of a number of artists, such as Pauline Cummins, Alannah O’Kelly and Anne Tallentire among others, who fought for recognition not only of individual female practitioners, but of the importance of recognising and representing female experience. Her association in the late 1980s and 90s with the Women Artists Action Group formed in Dublin in 1987, and with the Northern Ireland Women’s Action Group formed in Belfast the same year, contributed to a movement that sought to both recognise the pernicious nature of being silenced and to counteract its effects through solidarity. The need to counter the exclusion of women in supposedly defining exhibitions such as Directions Out in the Douglas Hyde and Making Sense: 10 Painters, 1963-1983 at the Project Arts Centre, (both held in 1987), meant mounting an urgent challenge to the institutional silencing of women through activism and in practice, creating group shows, agitating for more inclusion and recognition of women artists, and speaking directly as well as abstractly on women’s issues. This was made more urgent by the social and political climate of the time: the Eighth Amendment had been enshrined in the referendum of 1983 and there was everywhere the evidence of society’s violence against women with the false accusation and subsequent harassment of Joanne Hayes in the Kerry Babies case and the death of Ann Lovett both recent memories and Magdalene Laundries not yet a thing of the past.

2018 however, is a different moment. Although at risk of speaking from within one of those bubbles of optimism that emerge frequently but fleetingly in the history of the women’s movement; from our position as curators, we feel resonances between this work and a moment in which women are being considered not for their silence, but for speaking out [10]. Now, in a time of ‘Nevertheless, she persisted’, with #MeToo still raging and the referendum on the 8th amendment scheduled to take place later this year, the idea of being silenced is under attack like never before. Silence from a feminist position is no longer the condition against which we must struggle but instead is increasingly the condition of a recent and shameful past. Speaking out against sexual violence, on the murderous histories of Tuam and the other Mother and Baby homes around the country, on the cruelty of denying safe, legal abortion to women, women’s voices are voluble, angry and demanding change. Certainly none of this is new, but there is a ground swell of mainstream attention, a recognition of the realities of these sufferings in the media, and a sense of collectivism and support that provide hope that the issues raised will no longer be side-lined.